I did it again. I sent an article around to a bunch of people at work. Some of them work for me an probably feel obligated to read it or maybe even act upon it. I’ve become one of Those Managers – the ones who pass along trendy thought pieces to people who have more than enough inbound email. But this one was just too timely, too pertinent, too zeitgeisty. Here’s the quickest possible overview:

More choice is sometimes worse; less choice is sometimes better.

There. I said it. I voiced a repugnant, anti-democratic idea. I stepped on The Long Tail . I declared myself an enemy of choice and freedom and curly fries with cheese. Well, almost.

Let’s start with some material from the proximate source of my outrageous statement:

If some choice is better than no choice, and more choice is even better than that, then how can still even more choice — a seemingly unlimited array of choices in fact — not be a kind of decision-making nirvana where people make both better decisions and are happier about those decisions? Do not more choices and a greater number of options lead to better decisions? And if so, why then are people unhappy with their decisions even when a decision is a good one? Why do people feel regret even when they choose well?

And then there’s some more stuff and an excellent video going into some detail on why too much choice can lead to customers feeling ill-served even when they might be served better than with less choice. And then the design thing kicks in with the “learning to love constraints” thing. You should check all that out, but I want to pull the discussion back to the marketing and economics world where we can geek out.

I remember something from business school. I know, that’s shocking. I remember Prof. Drazen Prelec saying, with his rock-star hair and droopy slavic accent,

In the future, everything will feel like it is free.

What this grand statement meant is that marketers will figure out how to separate the pain of paying for things from the joy of receiving the things, not necessarily in time (although that helps a lot) but in mental space, and thus consumers will feel awash in free goods and services. Even though they won’t be free. Anybody offering something that doesn’t feel free will have a hard time selling against a competing offering that feels free, and so soon enough, everything will feel free. That was only 2001, and I think it’s well on its way to being true. Consider interest-only mortgages, free night and weekend minutes, Starbucks cards, EZ-Pass/FastLane, 0% financing, and $2,410,000,000,000 in consumer debt.

OK, let’s try to steer this ship back into port. I dragged Drazen in here because I want to riff on his formula and his ideas about hedonic utility in my rant about the goodness of restricted choice. I know, if I do that one more time I might have to start paying my alumni dues, but that East Campus project just rubs me the wrong way, it looks like it’s turning its back on Kendall Square.

Barry Schwartz says people with lots of choices are wracked with buyers remorse wondering if they made the right choice. Prof. Prelec says that people will be happier if they feel like they’re getting something for nothing even if they’re not. So I say that people will feel best if they get what they want but don’t have to make a lot of choices to get it. My formula is this:

The ideal number of choices is just one: exactly what I’m looking for.

But since different people look for different things, and some people don’t even know what they’re looking for, it falls to marketers and designers of information to engineer the choices to feel as close to this ideal as possible for each individual customer with the smallest possible number of alternatives – mass customization, extensive (but not invasive) customer profiling, recording and research, dynamic stores and product segmentation.

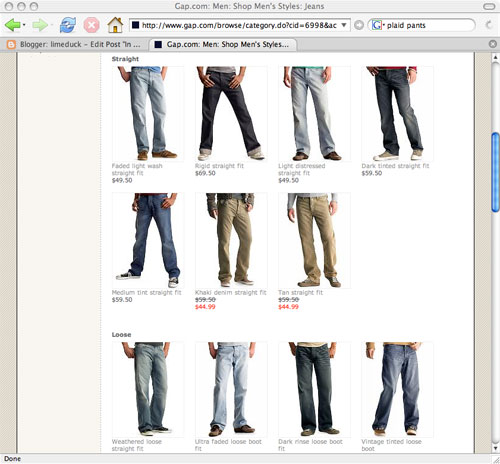

I want to walk into the Gap and see only clothes in my size. And only clothes in colors that will look good on me. And they should all be on sale. I’ll have a lot fewer choices and I’ll be a lot happier.

You are exactly right! As I’ve written (and often said), customers don’t want choice — they just want exactly what they want.

Joe Pine

Author, Mass Customization